Hollywood

via Orchard Street

by

Wayne Clark

Genre:

Historical Fiction

Deciding

that the hopelessness he sees around him on New York’s squalid

Lower East Side during the Great Depression isn’t for him, a young

man invents an alter ego with the chutzpah he hopes will make a name

for himself. In the process he accidentally ignites a war between the

Irish mob and a Chinese tong, learns to drink and finds love for the

first time. Will he and his alter ego ever reunite? They will have to

if he doesn’t want to lose the love of a beautiful Broadway

actress.

**Only

99 cents!!**

“THE goal,” young Charles Czerny scribbled in pencil, “was to become someone else. I am nothing,” he wrote. “i must contort myself.” He had once seen the word “contortionist” on a circus poster and looked it up. As euphoria invaded, he changed the “i” to a capital “I”.

“Nobody I know is anybody. And I mean anybody, up and down Orchard Street, and everywhere else.” Wielding with his new verb, he continued:

“They need to learn about contorting themselves, or they’ll always be kind of sad in life. They would probably like to tell someone that they’re always kind of sad, but they don’t have the words to say it, so to speak. But I do. For example, ergo... I learned that word in school. What I want to say is, ‘Ergo, you must contort your life if you want to die reasonably satisfied.’ You can’t ask for it all, can you. You have to send your mind up in a balloon and take a look around at the possibilities. When you see one that twinkles like a penny firecracker, adopt it. Say, ‘That’s me 10 years from now or whatever.’ Rewrite your life. I mean your future. You are what you are right now, you are what your whiney aunt says you are, but tomorrow, and all the tomorrows to come, well, that’s up to you. Make up a story, then live it.

He was pleased with his thoughts. There were a lot of them there. Those were the kind of thoughts he was sure writers have.

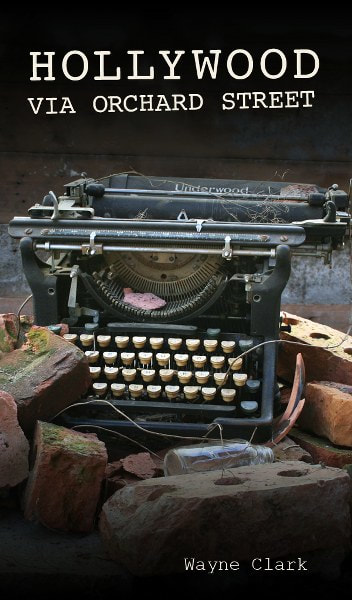

The next day he did not pick up his pencil. The new centerpiece of the salon that had always doubled as his bedroom on Orchard Street was, as of that morning, the most magical thing he’d ever possessed, an Underwood typewriter, an Underwood Model 2, which he had found hours before in the rubble of a fire on Mangin Street, above Delancey, near the river. The tiny street, Mangin, already had meaning for him because he vaguely remembered that his parents, or maybe just his father, had once lived there. His mind harbored echoes of someone saying “In the Mangin days.” He decided to contort that memory by telling himself it was fact that they both, mother and father, actually had lived in the place whose charred ruins he’d just scavenged. It didn’t matter that he could not remember his father. He must have lived with his mother at some point near the time of his birth. His mother never spoke of him.

When he got home to Orchard Street that afternoon with the typewriter, he fetched a cloth from his room and returned to the stoop to rub away the soot. It took a long time, and many neighbors stopped to observe him. Some would wish him good afternoon but mostly they remained silent. No one seemed familiar enough with the machine to admire it or ask how it worked or why he wanted it.

A sudden summer shower chased Charles back up the four flights of stairs to his room. When he was sure the Underwood Model 2 was dry—he always added “Model 2” in his mind because it made it sound like he had the latest, best writing machine in the country, guaranteed to bring results—he sat down at the table before it. Though he had nothing much he felt ready to state in black in white, he liked the fact that the typewriter was open-framed so he could see its inner workings. He saw an analogy with the inner workings of his own heart and mind, which, as a writer, he knew he would be required to explore. Yes, a good parallel, he thought, reaching for the dictionary, a relic from his school days. He made a mental note that “analogy” was spelled with only two a’s, not three.

Charles left school, PS 62 on Grand Street, in the middle of the seventh grade. There, as far as he remembered, he was good at poetry, mainly the required memorizing of stanzas but also at writing. Though the school-days memory was a candidate for future contortion, he believed deeply that he was good at it, the writing part. What he wrote was profoundly emulative of the works he doggedly memorized, all by 19-century guys from England. He knew that they were important works because no one he had ever met in his neighborhood, even all of New York, spoke like the poets did, words that were big and deserving of five or six definitions in his dictionary, or small but so obscure they were not even represented in the word bible. Perhaps the poets made them up. Yes, contortion, thought Charles. There was no shame in it. It wasn’t lying.

Certain that the writing machine would make him a writer, Charles decided to regard his current job as a temporary circumstance. Most people, especially since the Depression descended, were happy to have a job no matter how hard it was, and their greatest hope was that they would always have that job. Not Charles.

Nobody had ever asked Charles what his plans were. People in his neighborhood were too poor to have plans. Scraping by ate up the clock. Besides, he wasn’t an idiot. He knew he couldn’t say he was a writer until he’d written something and someone had put it in the paper.

Charles knew about papers. Delivering them to newsboys paid his rent of $14 a month. The smell of newsprint intoxicated Charles, who, at 24 years of age, had neither tasted alcohol nor a woman. As he wrote in his notebook more than once, this meant he had lots to do in addition to becoming a writer.

Award-winning

author Wayne Clark was born in 1946 in Ottawa, Ont., but has called

Montreal home since 1968. Woven through that time frame in no

particular order have been interludes in Halifax, Toronto, Vancouver,

Germany, Holland and Mexico.

By

far the biggest slice in a pie chart of his career would be labelled

journalism, including newspapers and magazines, as a reporter, editor

and freelance writer. The other, smaller slices of the pie would also

represent words in one form or another, in advertising as a

copywriter and as a freelance translator. However, unquantifiable in

a pie chart would be the slivers and shreds of time stolen over the

years to write fiction.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

No comments:

Post a Comment